There was a great article in

RollingStone 1076, the issue featuring a meditative Lil' Wayne on the cover.

The issue features a great piece written about Kris Kristofferson by the actor,

Ethan Hawke. I'm particularly fond of his performance in the

Dead Poets Society.

O Captain! My Captain!

One day I hope to get my students standing on their desks reciting poetry, and you absolutely can't go wrong with

Walt.

But back to Kris.

Kris is primarily known as an actor. His first role was in Dennis Hopper's pseudo-sequel to Easy Rider, The Last Movie.

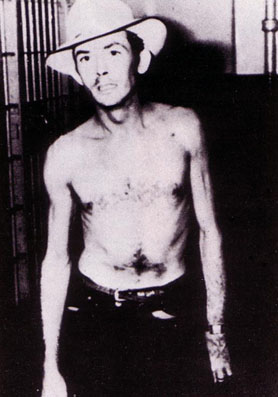

He and Bob Dylan redefined the western hero in Sam Peckinpah's Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid.

"For me [Ethan Hawke], has always been a part of the landscape of my country -- an amalgamation of John Wayne and Walt Whitman." According to Hawke, Kristofferson and Dylan were "claiming the country by seizing its most iconic art form, the Western, right out of John Wayne's and Glenn Ford's hands."

* * *

His big commercial break came in '76. He played a self-destructive, aging rock star in A Star is Born. However, Kristofferson's film career almost came to an abrupt end in 1980 thanks to Heaven's Gate, an anti-American Western. Hawke interviewed Martin Scorsese, who commented on the changing film industry in the 1980's: "The critical establishment ended that decade by making an example out of Heaven's Gate, eviscerating the film and everyone associated with it... They were done supporting individual expression in the movies."

In recent years, Kris' movie career has experienced a resurgence of sorts. He's the best part of the Blade trilogy, playing the gravelly and leathery Whistler, mentor to Wesley Snipes' tax-evading vampire hunter.

* * *

Kris, along with his other outlaw contemporaries -- Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, and others -- helped restore credibility to country music.

They embraced the self-destructive Hank Williams' lifestyle.

The "kick out the lights at the Grand Ole Opry" attitude of Johnny Cash.

This image stood in stark contrast to Chet Atkins' over-produced, squeaky clean, polished Nashville image and sound.

True fans of country music were exhilirated.

***

Kris' success seems to stem from his charisma, which affects his performances as an actor and songwriting-musician alike.

Here are some random facts about Kristofferson:

He received a Bachelor of Arts in Literature from Pomona College.

He was a Rhodes scholar. He studied William Blake and William Shakespeare at Oxford University.

He joined the army and became a helicopter pilot.

After completing a tour of duty, he was offered a position teaching literature at West Point.

He turned this offer down and moved his family to Nashville. Initially unable to succeed as a songwriter, he became at janitor at a studio owned by Columbia Records. He was present while Dylan recored his landmark album, Blonde on Blonde.

While working as a janitor, Kristofferson also worked part-time as a helicopter pilot flying out of the Gulf of Mexico.

He landed a helicopter in Johnny Cash's backyard to ensure that the "Man in Black" himself would listen to his demo tape.

Kristofferson emulated his hero, the late, great Hank Williams, a man who according to Kristofferson, belonged in the company of Shakespeare and Blake.

Funny.

A drunk, illiterate hillbilly in the company of Shakespeare?

Leonard Cohen agrees.

"Tower of Song."

Well my friends are gone and my hair is grey I ache in the places where I used to play And I'm crazy for love but I'm not coming on I'm just paying my rent every day Oh in the Tower of Song I said to Hank Williams: how lonely does it get? Hank Williams hasn't answered yet But I hear him coughing all night long A hundred floors above me In the Tower of Song I was born like this, I had no choice I was born with the gift of a golden voice And twenty-seven angels from the Great Beyond They tied me to this table right here In the Tower of Song So you can stick your little pins in that voodoo doll I'm very sorry, baby, doesn't look like me at all I'm standing by the window where the light is strong Ah they don't let a woman kill you Not in the Tower of Song Now you can say that I've grown bitter but of this you may be sure The rich have got their channels in the bedrooms of the poor And there's a mighty judgement coming, but I may be wrong You see, you hear these funny voices In the Tower of Song I see you standing on the other side I don't know how the river got so wide I loved you baby, way back when And all the bridges are burning that we might have crossed But I feel so close to everything that we lost We'll never have to lose it again Now I bid you farewell, I don't know when I'll be back There moving us tomorrow to that tower down the track But you'll be hearing from me baby, long after I'm gone I'll be speaking to you sweetly From a window in the Tower of Song Yeah my friends are gone and my hair is grey I ache in the places where I used to play And I'm crazy for love but I'm not coming on I'm just paying my rent every day Oh in the Tower of Song.

As a musical genre, country music is ripe with gothic lyrics and subject matter. One of my favorite country songs is "Psycho." Penned by Leon Payne, the song is masterfully interpreted by Elvis Costello, an Irish New Waver (and my favorite lyricist). The song deals with murder and insanity and possesses a uniquely Southern flavor.

As a musical genre, country music is ripe with gothic lyrics and subject matter. One of my favorite country songs is "Psycho." Penned by Leon Payne, the song is masterfully interpreted by Elvis Costello, an Irish New Waver (and my favorite lyricist). The song deals with murder and insanity and possesses a uniquely Southern flavor.